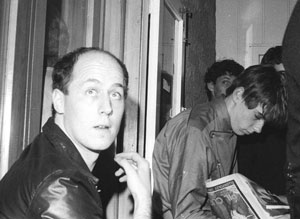

Joe Strummer, somewhere in the USA, talking to Michael Hutchence: Wow it must be strange to be a sex symbol

MH: Well, you’re Joe Strummer..

JS: No I was never a sex symbol. I was just a spokesman for a generation.

I’ve just finishing Chris Salewicz’s Joe Strummer biography, Redemption Song, which I found to be an engrossing and mighty read, trawling with some detail through the life, both high and low, of a man who quite clearly was one of the most important musicians, from any genre, of the past half century. He had a huge impact on me, and indeed, the deaths of only three musicians have bought a tear, the other two being Beatles.

The day Joe died I had a radio show to do and played Bankrobber on the show. It being a dance station I had a couple of texts wondering why I was noting the death of a rocker. I tried, in the most positive way I could, to explain that the dance revolution of the late 1980s was a direct outgrowth and result of the wee revolution led by Joe a decade earlier. It was Joe Strummer, the rest of The Clash, and the likes of John Lydon who made the rule that there were exactly no more rules, which snowballed into the indie revolution, garage electronica, the post punk scene and the club explosion.

You’re a DJ?...thank Joe Strummer.

After I finished the book I watched, with Brigid, the Julian Temple doco, The Future Is Unwritten. It was beautifully crafted and quite moving (although it tried a little too hard, as Temple does and I think I got quite a bit more of the man from the book) but we both agreed as the movie ended that there was much about Strummer that we would both have rather have not been reminded of. And that, despite the critical success of his post Clash band, The Mescaleros, you couldn’t help but feel that the singularly worst decision he took in his life was to fire Mick Jones in 1983. After that he seemed to spend the rest of his life trying, sometimes without direction, sometimes with, to grasp past and lost glory. It felt a bit empty, and the one time I saw him live in this phase, I felt the same. You couldn’t help but think that both of them were slightly workman without the other.

Why am I writing this now? Well aside from the book, which, as I say, I recommend above the DVD of the doco as having a little more flesh and substance, and having a little less of the mouth open idolatry, I’ve been thrashing the recent live Clash album, recorded at Shea Stadium, some 11 months before Jones got the boot.

The Shea concert, supporting The Who, is the stuff of legend. It was the moment that The Clash looked likely to take the USA and the world by storm and become the heirs to bands like The Who and The Rolling Stones. They didn’t of course, they imploded and, for our sins, we got U2 instead.

I’ve got a couple of other live Clash bootlegs, one from mid 1977, all snarl and punk, and one, although unlisted, from I think the (in)famous Bond’s season a year before this and both of those, for want of a better word (and there must be one, I just can’t think of it) rock.

Then there is the earlier live album From Here To Eternity, which largely fails because it tries to hard to be too many things (although the Ska version of White Man recorded in Boston around the same time as this album is a killer) and is a live compilation rather than a set..

But the Shea Stadium show works because it is a band on the edge, a band under silly pressure, and it captures the freneticism of the moment before it all goes pear shaped.

Starting with a very 1977 sounding London Calling, and then stomping into Eddie Grant’s Police on My Back, it roars ahead like a Ramones live set, with only 45 minutes to get through the song before The Who. It’s a band on a short fuse in more than one way and all the better for it.

And then, four songs in, it drops into the much written about Magnificent 7 / Armagideon Time / Magnificent Dub, premiered a few dates before this show, which takes you to the core of where this band had got to, five years after White Riot.

‘Now play it like a twelve inch’, says Strummer, and admits to the band stealing the rhythm one night from the Black New York grooves that Jones was so enamoured of, as it drops from the funk groove into a mighty Armagideon Time skank, much tougher and looser than the single version, before jumping back into the 12” dub mix of The Magnificent 7. It’s along way from even the pointer of Police & Thieves on the first album, and it’s one of these reasons why the band’s implosion was a such a sin, at least from a fan’s point of view.

After that little journey the album hiccups a little with a slightly plodding Rock The Casbah (which, lets face it, was one of their lesser tunes anyway), and set filling Train In Vain but then tears in into a scorching quartet of tunes, the magnificent Career Opportunities (also on the earlier live album, and also on a the CD as a video…only Joe Strummer could possibly have looked cool in a coonskin cap, although that may be subjective), a couple from from London Calling, and then English Civil War, as strident as it needs to be when one considers both the venue and the war in the band, which had already seen Topper Headon sacked.

But what pulls this album together, and makes it one of those very rare beasts, a live album that works without the visuals, is the sheer force of Strummer the very British showman. With the genius of Mick Jones’ melodies, and his own very raw almost stripped Staxish vocals, and lyrics, it’s Strummer the great rock poet of the post Lennon era who makes the record soar in a way that a thousand U2 albums could never approach. It was Strummer, the populist revolutionary punk poet who waved the flag, beat the drum and pulled it all together just for a brief few years before it disappeared forever, not just for us but for him.

Where’s the hair gel? We can’t start the revolution without hair gel!

Joe Strummer, 1982