I had a day of two halves yesterday as I straddled the fairly wide gap between two wildly different worlds. One was real, the other slightly surreal.

At dawn I found myself in the grounds of the Australian Consulate, who also represent New Zealand’s interests (or, mostly, lack thereof based on the number of compatriots you see here now) in Bali. Our daughter, we found out earlier in the week, had volunteered to represent her home country as the flag raiser at the ANZAC Dawn Parade.

Sadly neither Brigid or myself are morning people, and squirmed a little at the thought of a 4.45am rise.

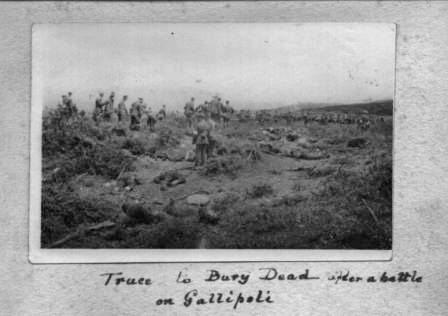

I’m not belittling the lost lives of those who are remembered on ANZAC Day. I’ve stood in the Auckland War Memorial Museum on several occasions and looked at the name of my great uncle, Julian Cornelius Brook, who was fatally wounded at Gallipoli (and who took the above shot), with a mix of respect and great sadness. The profoundness of ANZAC day dwarfs all of us.

I explained that, as best I could to Isabella, but at thirteen, as the bulletproof years start, it's not that easy.

And its still not that easy to throw the dogs off and pull oneself from a comfy bed before sunrise. But we did.

However to be honest, as moving the last post is at dawn, as the flag goes to half mast, it was all a little odd. Firstly we were in Bali, in other words, in Indonesia, where ANZAC not only means nothing but the country, for all its multitude of holidays, doesn’t have a great tradition of remembering young people lost in foreign fields for, often, long forgotten causes and what now seems like foolish leaders involved in petty political manoeuvring for pointless advantage (could WWI be described any other way?). Indeed, many in Indonesia, especially the younger, would rather forget their dubious military adventures and with good reason. The holidays here, instead, are either religious in nature or remembering the battles against the imperial forces partially being remembered by ANZAC Day. The Commonwealth forces are not well remembered here, as they were the bad guys in 1945.

With that in mind I was pretty sure that the Indonesian General placing a wreath was as confused about what was going on as he indeed looked.

Then we had the choir, Balinese, and in wonderful voice. But there is something rather bizarre listening to an Indonesian choir singing God defend New Zealand, in Maori, in Bali. Even in New Zealand the words to that strange song seem misplaced now, but here……

That bizarreness was accentuated by the consulate itself, which has been sculpted, behind massive security gates, walls and electronic devices, to look as much like a part of Canberra as possible. I’ve seen nothing like it’s rolled, manicured lawns in this country before…it was like walking into an expat’s misty fantasy memory.

And then we have the consul’s car...a new-ish top end BMW. Aside from the snarl from a leaving Ocker vet asking ‘why isn’t it a Holden’, it seems odd that, considering the massive security at the consulate, arguably quite reasonable when one thinks of the recent past, the head guy should drive a car that so obviously stands out from the masses on the jalans.

Of course, it was superbly done…the ceremony that is, and the consul and staff gave everything expected of them, and was followed by a good ocker breakfast barbie on the rolling lawns. In Indonesia? Who us?

Of course, it was superbly done…the ceremony that is, and the consul and staff gave everything expected of them, and was followed by a good ocker breakfast barbie on the rolling lawns. In Indonesia? Who us?

So from Denpasar, after a bite with some friends, we then travelled north to a place somewhere between Giyanyar and Petak, to our gardener’s wedding. He, Gustu, is a lovely guy, not very good as a gardener but he came with our house and we’ve never had the heart to let him go. I just like chatting to him and seeing his smile. And now, aged just 20, he’s marrying his girl, Putu, aged just 17. We’re not sure exactly why, but his niece, aged 19, said ‘He’s too young’, and there is no doubting his worried expression.

It was a million miles from the ANZAC dawn and the rolled western styled lawns. This was the Bali that tourists never see, which, to be fair, is the bulk of the island. There was little English spoken, no tour buses and no hawkers. This was a trip back to the northern hills where nothing much has changed in over a century, apart from the click of a digital camera and the odd cellphone, to the family compound.

Change may be coming though, as we passed the workmen on the winding narrow road digging to install a small part of the incredible 58,000kms of fibre optic cable going through Indonesia under Project Palapa Ring, whilst first world NZ argues over its tiny infrastructure project.

Change may be coming though, as we passed the workmen on the winding narrow road digging to install a small part of the incredible 58,000kms of fibre optic cable going through Indonesia under Project Palapa Ring, whilst first world NZ argues over its tiny infrastructure project.

And I guess, like China, that infrastructure is a part of the thing that will take this massive country to a completely different time and place. And like China, it will happen without anyone expecting it.

But at the moment I’m still struggling through a country where, bugger the internet, most people can’t read a map primarily because the Dutch deliberately kept the populace uneducated for their own purposes, and successive governments have done little more, so there is no tradition of such. Thus we got very lost getting to Gustu’s upacara because the map on the invite rear bore no relationship to the actual route  and we were, after we left the main road, in the hands of old people sitting on the side of the road, many of whom no doubt, had rarely left their village, pointing us in vague directions towards the next village. It was only about 40km from our house but took several hours and several stunning but incorrect roads before we stumbled upon the compound in Desa Babakan.

and we were, after we left the main road, in the hands of old people sitting on the side of the road, many of whom no doubt, had rarely left their village, pointing us in vague directions towards the next village. It was only about 40km from our house but took several hours and several stunning but incorrect roads before we stumbled upon the compound in Desa Babakan.

Tourists are always going on about the ‘real’ Bali (by which they often mean Ubud for gods sake) but here in the hills, off the roads, up the muddy trails is a world that few ever see, and yet that is how about half the population of the island still lives, and I always feel like a voyeur when I catch a small, but always welcoming, glimpse of what this island used to be like, and its little like the ‘real’ Bali sold to the masses.

How long this world will survive, as the likes of Denpasar more and more becomes the day to day reality of Bali for so many Balinese, and the villas and technology creep north and into the valleys and hills, I don’t know.